Civility as Radically Moderate Civic Education

"I don't like that man. I must get to know him better."

Abraham Lincoln

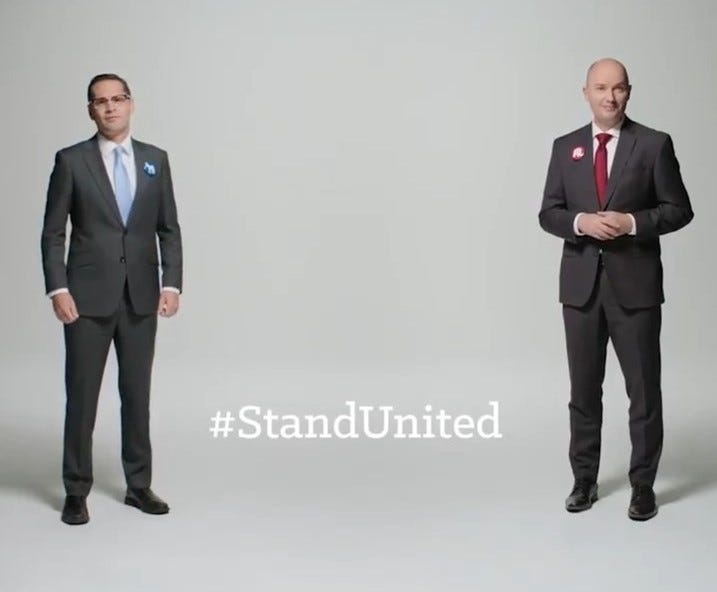

Civility seems to be making a comeback, or maybe just everyone is desperately hoping it will. But there are reasons for optimism, like the candidates for the Utah gubernatorial race engaging in a series of charming ads together in which they focus on what brings us together as Americans rather than what tears us apart. The ads aren't substantive, but that's not really the point. In a decade where negative ads have dominated election cycles, the idea of two opposing candidates sharing ad space and dollars to make a pitch for a more civilized world feels a little like hanging out with a box full of kittens for a few minutes. A much needed break.

But knowing that we don't like incivility or crave civility doesn't tell us about why civility matters in the first place. Our position here is that civility isn't just a way to interact with others, but it is in itself a kind of civic education that helps us understand the communities we share together better. It is both a tool for interaction and a tool for powerful change.

Civility is both a tool for interaction and a tool for powerful change.

But first, let's start with a basic definition. According to good old Oxford language on Google, the term "civility" has its roots "in Old French from the Latin roots from Old French civilite, from Latin civilitas, from civilis ‘relating to citizens’ (see civil). In early use the term denoted the state of being a citizen and hence good citizenship or orderly behavior." What's most interesting about that definition for our purposes is the "civilis" part: "relating to citizens." In effect, civility relates to how we interact with each other as citizens engaged in a common, communal life. It's not merely politeness, but instead a broader way of engaging with those with whom we share decision-making about our communal present and future.

Unsurprisingly, there's a link between incivility and polarization. The more polarized we are, the more uncivil we become, in part because it makes it easier for us to demonize and dehumanize the other side (committing the fundamental attribution error along the way). It's a vicious cycle too because the more we see the other side as vicious and evil and the more uncivil we become as a result, the easier it is to dismiss us as vicious and evil too. So we have a feedback loop of incivility --> polarization --> increased incivility --> more polarization.

Really? Civility now?

We get it. Civility can be a dirty word. Some characterize it as a cousin of dishonesty or hypocrisy, as when Martin Luther King Jr. pointed out that polite white Northerners were in fact more dangerous to his cause than Southern KKK members. If civility is mere politeness a civil person may still be trying to destroy you.

Others criticize civility because they think it's being applied too broadly. Maybe there are areas where civility just can't play a role or areas where civility isn't really the lens we should be looking through. Is Mitch McConnell being uncivil by holding the Supreme Court nomination process hostage to partisan politics or is he merely engaging in politics as usual?

Others criticize calls for civility as tone policing, or a way of controlling the narrative around serious injustice while marginalizing the contributions of angry people who are angry for good reasons.

Those criticisms can be valid and there's nuance to when civility matters and when injustice or harm becomes so great that there's no legitimate civil response. We're not here to solve that problem, but instead to think about why civility, despite its inappropriateness in some potential contexts, still matters most of the time. And whatever the definition, most Americans believe incivility is a real problem.

We think civility matters in a deep and existential kind of way. We've mentioned this before, but we have to learn to live with each other in community no matter what happens at the end of an election, and the more uncivil we are the harder it is to restore community and build a better society for everyone. Civility, at its core, is about being able to be in conversation with people we disagree with without resorting to threats or violence. It's absolutely necessary for any kind of reform or change (though we don't think it's always sufficient).

Civility also makes it more likely we'll change minds. While it's now controversial to say this, peaceful protests are more influential than violent ones, and conversations in which a trusted person gently challenges someone's beliefs are much more likely to change those beliefs than an angry person on the internet. Facts don't change minds, but social networks do. And those social networks are most influential when they use civil conversations instead of ideological bludgeons.

Civility as a National Security Issue

There's another way in which incivility eats away at the heart of American democracy. Incivility opens us up to attacks from the outside, making us vulnerable to trolls and those who would exploit our divisions.

As we've become more polarized we've seen increasing numbers of attacks on the fabric of American democracy, using incivility as a weapon. The most recent example was threatening emails sent to Democrats that seemed to be sent from the Proud Boys, the alt-right group Trump ambiguously told to "stand down and stand by" at the first presidential debate. It turns out those emails were in fact sent by Iran in an attempt to undermine American trust in the outcome of the election.

Unfortunately, these kinds of attacks are not new. We know from the 2016 election that Russia created profiles of fake Americans on Facebook, whose job was apparently to engage in uncivil disagreement and piss people off. In general, Russian interference in the 2016 election existed in part to support Donald Trump, but also just to sow chaos and discord in the American electorate by emphasizing polarizing issues and stoking division and anger on areas of deep division.

What Russia, Iran, and China all understand that we're just learning is that the angrier you can get people at each other, the less they trust each other and the less they trust the outcome of democratic procedures. Before the internet age, if the other side won we might not like it, but we didn't question the entire process. Now though, if the other side wins we question democracy itself. Not only have the stakes never appeared higher thanks to skyrocketing polarization, but the other side has never seemed sketchier. Stories about gerrymandering, voter intimidation and confusion, the role of money in elections, fears of election mail fraud and possible tampering (and other kinds), emphasize increasing levels of mistrust in whether each side abandons democracy enough to manipulate the election. What's important to notice about all these claims (including the behavior that animated them) is that in each of these cases people are viewing the other side not as fellow citizens but as enemies. We've lost civility in part because we've stopped viewing each other as engaged in a common project. We're no longer citizens, we're combatants.

We're no longer citizens,

we're combatants.

In effect, Russian, Iran, and China have found the fracture points in American society and are drilling down into them with frightening accuracy and intensity. Or maybe a better way of describing is is that incivility is a lot like friction on skin. At first it doesn't make much difference. It might even feel good to get that last word in or to land that perfect political insult. But over time, that friction starts irritating the protective mechanism of the skin. It creates an open sore. And the more the friction of incivility keeps working at it, the wider that wound gets. And our enemies see that wound and know they can pour in infection that will potentially destroy the whole civil organism. It might sound histrionic, but incivility is the first step toward civil war precisely because it is the first and most important way we stop treating fellow citizens as citizens at all and instead as enemies to be destroyed. And our real enemies know this and they know incivility works to open those wounds and encourage them to fester. And for a lot of observers, there's legitimate cause for concern.

All this is well and good, you might say, but what does it have to do with Radical Moderation? Civility might be a virtue, but that doesn't make it a radically moderate one. Well, we disagree. We think civility is in fact Radically Moderate and because we like lists a lot, we'll do our usual principled rundown.

What's Radically Moderate about Civility?

Civility isn't just about politeness. It's actually a mechanism for doing all sorts of amazing Radically Moderate things. It's a kind of superpower that not only allows us to investigate deeper and forge new relationships but helps us understand those relationships in a more complex way. What's great about civility is that it is both a method for engaging with each other but also an investigative tool that makes us better citizens in the end. Here's how!

Civility leads to deeper understanding because in its most complex form it requires a deep humility about other people and their motives. Civility is best animated by the belief that we really don't know why people believe the things they do but we want to find out. Starting from a position of humble curiosity is much more likely to lead to civil dialogue than walking in thinking we know the whole story. But even more than that, the humility that civility requires gives us more access to knowledge of the other side.

The humility that civility requires compounds into a deeper understanding and brings with it an appreciation of complexity. Human communities are diverse and require complex solutions. Drilling a single or simple solution over and over isn't going to convince people we're right, it's just going to convince them we don't understand what's going on. Asking curious questions and treating other people as human beings helps us better understand the full range of issues that are at play.

Once we understand the complexity at play, civility requires a respect for diversity because not everyone lives the way we live and not everyone values the same things we value. Assuming that everyone must believe the same things we believe is both uncivil but also wrong! Once we've asked those curious questions we're likely to find out that people care about a lot of different things and our own approach might be better if we took those differences into account.

As the penultimate step in this process, civil discourse requires that we be open to tradeoffs and alternatives we had not thought of. Precisely because the world is complex and people care about diverse things, we start to realize that caring about one thing a lot might require tradeoffs in other areas we also care about. Resources we want to spend in one area will require pulling from or rethinking another. Civil life is about balance, not perfection. All of us will do a certain amount of harm and a certain amount of good in our time on this planet and it's one of our goals to make sure that balance works out on the side of the good. Civility asks us to consider that the person in front of us is doing her own complicated balancing act too.

Finally and perhaps most importantly civility asks us to recognize the fundamental humanity of the person on the other side. Whatever we think of their political positions, whatever we think of the choices they make in their lives, each of them represents an incredible miracle of evolution (and God's providential love if you go for that sort of thing). The opinions of other human beings matter precisely because they are held by other human beings. And no matter how much we may disagree, our listening for just long enough is one way to get insight into how different people think, which is perhaps the most crucial and overlooked task of citizenship.

Our listening for just long enough is one way to get insight into how different people think, which is perhaps the most crucial and overlooked task of citizenship.

As part of this civility-as-civic-education view, it's also worth stressing that civility does not and should not require that we talk about politics all the time. In fact, civility requires a prudence about when potentially heated conversations should occur. In some situations avoiding political or hot-button issues is the civil thing to do. You don't need to talk about politics with the guy at the gas station unless you know him and know he loves arguing while making change. Similarly, there are some people who we know we can't be civil with on specific issues, so it's best to just avoid those issues if it's a relationship worth preserving in other ways. There are also situations in which civility requires that we put aside politics or really any disagreement and instead simply be together as humans. In fact, part of civility may be the recognition that politics should play a very minor role in our civil lives together and sometimes the less said about it the better.

What you can do:

There’s only one rule that I know of, babies — ‘God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.’

Kurt Vonnegut

Since we don't have a lot of power over other people, particularly people in power themselves, we're pretty limited to what we can control, which is ourselves. So it should come as no surprise that most of the guidance for creating a more civil society comes down to individual choice. We'll start with the obvious and then work toward the more complex.

Work to be civil in your own life. This is hard, but it's necessary. If you're really struggling, try to think about how you're going to approach conversations before they start. Do you always end up yelling at your racist Uncle Joe? Spend some times figuring out how he gets to you, if there's a way to redirect your anger, and whether the conversations you have with him on certain topics are worth having at all. If you can't be civil or if someone else is simply returning your civility with incivility, it's time to disengage. You don't need that in your life, so don't let it in. Either create boundaries around the relationship or, if that won't work, reassess the relationship itself.

Model civil disagreement to those around you and to your kids. Ask curious questions: "Interesting! Can you tell me more about that? What led you to that position?" Sometimes it's also really important to say "hey Larry, I really respect you as a friend/neighbor/fellow citizen, but I disagree. Here's why." And because we need to protect ourselves from the damage the ooze of politics can create, we need to be able to model how to exit these conversations too. "Betty, I think I have a better understanding of where you're coming from. We won't agree on this and this probably isn't the best place to discuss this further, so let's change the subject. How's the garden this year?"

Watch your tone. Yes yes, we know, this is unpopular, but tone matters. We Radical Moderates (try to!) cultivate a cheerful and curious tone in our debates with those around us in part because it helps other people feel comfortable but also because it reminds us what we're doing. This is not a war. This person we are talking to is not our enemy. Whatever terrible and stupid positions they're defending, they're still human beings. And maybe we find out when we dig a little further that their positions are less terrible than we thought. Or maybe we don't! But we won't find out if we start out with incivility. When we find ourselves unable to control our tone that's usually a good signal that this isn't the conversation to be having at this time in this place with this person. And that's ok.

Don't watch other people's tones for them. This part is just as important. If someone is getting upset or a little too *fill in the blank* for your preferences, it's not your job to shut that down or tell them how to behave or feel. People have a range of experiences that will affect how they think about and react to things. Some of these reactions might be illegitimate, but a lot aren't and it's not really your job to figure out which is which. The only job we have in our dialogue with others is to make the best case for our position in a way that's compatible with the humanity of the person across from us. If someone is too agitated or upset or sad for our tastes, we don't get to tell them they're wrong, but we do get to decide whether we want to continue in the conversation. Sometimes in conversations about complicated and emotional issues, it's not the right time or place or person to be having this conversation with and that's ok. Not every conversation can or should lead to everyone civilly agreeing or agreeing to disagree. Sometimes the result of a conversation is that we find out that people feel very very strongly about something and then it's our job to step back and think about why.

That's it from us! As always, we want to hear from you! How do you work to produce civility in your life? What kinds of tools and triggers do you use to keep conversation civil? When do you think civility fails? Tell us in the comments!

Some great resources to check out: (we'll be adding to this over time):

Jonathan Haidt's project on civility

Heterodox Academy (also Haidt-based), devoted to viewpoint diversity in the academy