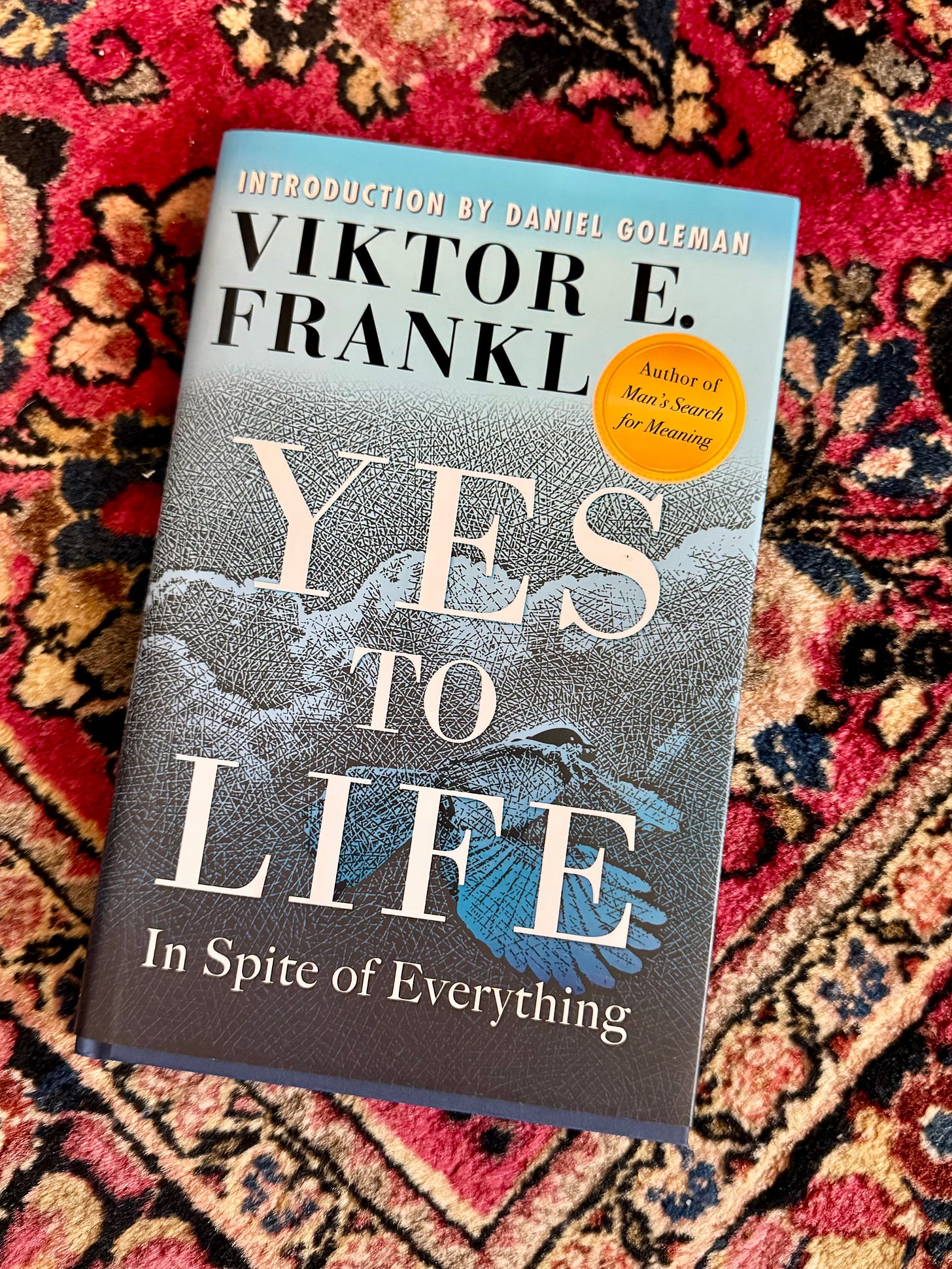

Radically Moderate's Book Corner: Yes to Life, In Spite of Everything

Viktor Frankel's profound optimism in the face of unimaginable tragedy

..there is only one thing left for us to do: to act; namely, to act in our everyday lives.

- Viktor Frankl

Watching Los Angeles burn while gearing up for a divisive inauguration has made for a difficult week for a lot of Americans. And that’s on top of the personal challenges that life is throwing at some of my friends and colleagues, including illness and loss, that are just the reality of being human.

Oddly enough, the suffering in L.A. and elsewhere this week makes it the perfect opportunity to crack open a book I’ve had sitting on my shelf for over a year but haven’t had time to read, Viktor Frankl’s Yes to Life, In Spite of Everything.

This week seemed like a good “in spite of everything” week to explore some healthy realistic optimism and throw together some almost-coherent thoughts about Frankl’s work and what I got out of it.

(As a brief warning to my rigor-minded readers: This will not be a comprehensive overview of Frankl’s work, which I’m 100% unqualified to attempt. I’m just pulling out some lessons that I think are relevant for the trying times in which we find ourselves. Another partial disclaimer: Frankl’s most famous work is Man’s Search for Meaning, which I haven’t actually read yet. I picked up Yes to Life for weird internet algorithm reasons including that it was reviewed recently now that it’s in English for the first time.)

Viktor Frankl, as you may already know, is famous as both a psychotherapist and Holocaust survivor. The lectures that comprise Yes to Life were given less than a year after he was freed from from a Nazi labor camp and months after learning that his parents, his brother, and his wife (by some accounts pregnant at the time) had all died in the camps before they could be liberated.

When he arrived back in Vienna, he threw himself into work despite having, in his own words to a friend, “nothing more to hope for and nothing more to fear.”

While I provide some pull quotes below, I highly suggest reading his work. He’s a lively writer and this work in particular toggles between anecdotes about concentration camps and mentally ill patients and yet somehow the reader comes away deeply optimistic instead of horrifyingly depressed. It’s quite a feat.

Man’s Search for Meaning, written later and coming out of these lectures, is likely a more polished work and probably a better starting point, but I enjoyed reading Yes to Life a lot. Either likely works.

Suffering and Meaning

As a quick and dirty summary, Frankl’s overall argument, which is fleshed out in more detail in Man’s Search for Meaning, is that meaning in human life can be found in three ways: Creating, experiencing, and enduring.

Creating can include creative, professional, or personal creation. Anything from art to writing to (one assumes) bringing children into the world.

Experiencing can include the experience of art, music, or nature, but also the experience of other human beings, whose existence itself gives life meaning. One quote I found particularly moving, particularly given how recent Frankl’s losses were at the time he was writing, described this kind of experience, one that most parents feel in their souls:

the fact that this person exists in the world at all, this alone makes this world, and a life in it, meaningful.

A Buddhist might question whether hinging meaning on transient experiences, including experiencing impermanent humans, is a good idea. But Frankl makes a kind of Eastern pivot, emphasizing that the act of generating meaning is a continuous process, not a static state:

the meaning of life can only be a specific one, specific both in relation to each individual person and in relation to each individual hour: the question that life asks us changes both from person to person, and from situation to situation.

If one lost the person who gave one’s life meaning, as Frankl did so horrifically, it then becomes our task - even our responsibility - to either make meaning out of that loss or to find another way to make meaning moving forward. There’s some resonance with Zen thought here, which I was not necessarily expecting.

Frankl’s almost frantic work ethic after he returned to Vienna, seeing patients, writing, and speaking, with his entire world torn apart and almost his entire family dead, offers one example of this process of continuing to make meaning when all hope is lost in action.

But he provides other examples in the book, including patients of his who lost their ability to do the things they loved as a result degenerative diseases that eventually robbed them of all their abilities. These patients found meaning in taking a final stand in their final hour and facing death with courage. In the case of one patient, a graphic artist who eventually lost the ability to move altogether, his final act of creating meaning was attempting to limit the inconvenience his death would create for hospital staff in his final hours (61).

Finally, and this is the perhaps the most important aspect of his writing given his terrible experiences, is that meaning can also be found in even the most profound suffering, simply by enduring it.

Note that Frankl doesn’t support suffering for the sake of suffering, but he does find that when we are faced with what he calls “necessary and unavoidable” suffering, the last act of will we can offer is to make meaning out of it:

…fate is part of our lives and so is suffering; therefore, if life has meaning, suffering also has meaning. Consequently, suffering, as long as it is necessary and unavoidable, also holds the possibility of being meaningful. (40).

Frankl’s experiences in the death camps taught him that meaning often becomes most obvious and most profound at the very end, when we feel as though all hope is gone. Perhaps not coincidentally, Tolkein, writing around the same terrible time, summarized the same thought in the Middle Earth proverb “Oft hope is born, when all is forlorn” that Legolas offers in Return of the King.

It’s a theme with resonance across human history. And it has a profound reverse version as well. In Oedipus Rex, the chorus sagely warns us that no man should be considered happy until he is dead, because we don’t know what suffering can befall us in the last moment. Oedipus, once a great king, finds himself impoverished, guilty of incest, and blind in the bargain.

But Frankl is more hopeful and positive than the Greeks (which isn’t hard), concluding that even if we do find ourselves facing profound loss at the end of life - as Oedipus did - even in the face of ultimate and complete loss we have the opportunity to make one final stand in creating meaning for ourselves out of the wreckage.

A final lesson we can glean from Frankl’s discussion of suffering is that while his account is deeply individualistic, it’s also deeply humble at the same time. The goal of making meaning is not to elevate the individual over others, but instead to help the individual find meaning in life and endure - when necessary - the suffering that life so often brings.

As part of this Frankl is clear that any comparative “Olympics of suffering” is a useless and ultimately damaging game. He discusses a friend who felt guilt comparing his experience of the war to Frankl’s because the friend “only” fought at Stalingrad. Frankl responds, in part:

…it would be pointless to speak of differences in the magnitude of suffering; but a difference that truly matters is that between meaningful and meaningless suffering… this difference depends entirely on the individual human being: the individual, and only that individual, determines whether their suffering is meaningful or not” (101).

The question therefore of whether a concentration camp victim suffered more than a soldier at Stalingrad is a meaningless one, because the relevant variable is missing: what that particular person did with their suffering and how they created meaning out of it.

The irrelevance of comparison or relative suffering is related to the fact that Frankl doesn’t claim any particular virtue for surviving the death camps. The meaning his life carries does not hinge on the fact that he survived. The meaning of life is completely disconnected from any external outcomes at all.

In fact, to avoid drowning in survivor’s guilt, one has a responsibility - both to those that died and to oneself - to pick up the pieces and keep finding meaning. Finding meaning in life is not simply something we want or need for ourselves, but it’s also something we owe to other people.

This is especially true, he notes, because

…we survivors knew very well that the best among us in the camp did not come out, it was the best who did not return!

In fact, Frankl says it’s precisely the “undeserved mercy” of his survival, while his family and so many other good people died such horrific deaths, that requires the absolution of collective guilt, even from those who turned away and who knowingly ignored what was going on. It’s a profound appeal to grace rooted in deep humility.

Diverse Paths to Meaning

One final lesson I took from Frankl’s lectures this week is that it doesn’t matter what space we’re in, we can always make meaning in our lives and support those around us.

Frankl tells the story of a tailor’s assistant approaching him after a talk and saying “it’s easy for you to talk, you have set up counseling centers, you help people, you straighten them out; but I - who am I, what am I - a tailor’s assistant. What can I do, how can I give my life meaning through my actions?”

I’ll admit to grappling with this kind of futility/imposter syndrome a fair amount, especially recently. I’m still not entirely sure how or even whether my writing contributes to making people’s lives better in any meaningful way. And I’m occasionally frustrated by the naval gazing that academia encourages while at the same time being frustrated at myself for not being out in the world doing more.

But Frankl’s response is both affirming and honest:

it is never a question of where someone is in life or which profession he is in, it is only a matter of how he fills his place, his circle. Whether a life is fulfilled doesn’t depend on how great one’s range of action is, but rather only on whether the circle is filled out.

For now, at least, I’ll take solace in Frankl’s advice. Whatever else I could be doing, my job is to make meaning within my given circle now. Writing is also, of course, an act of creation and one I find deeply meaningful for myself. I have some reason to hope that a small circle of others finds it meaningful too.

But Frankl’s overall point is that we cannot compare our contributions - our creations, our experiences, our endurances - to other people’s. What we offer is unique to us and, even more important, Frankl would argue, the meaning we make of our own lives is entirely up to us. It doesn’t depend on any outward success or number of people reached.

Frankl’s goal is precisely to release us from this kind of fruitless comparison. Rather than searching for meaning outside of ourselves, he wants to encourage us to say “yes” to life because it’s worth it both despite and perhaps even because of the suffering it entails.

For those of us suffering this week and for the others of us who are feeling guilty about not knowing what to do or not doing more in the face of human suffering, Frankl provides a final piece of advice:

..there is only one think left for us to do: to act; namely, to act in our everyday lives.

Radically Moderate Takeaway

This one is short and simple: Go ahead and say yes to life (in spite of everything) this week. And grab some of Frankl’s work and dig in.

That’s it for me this week! Go make some meaning today, whether by creating, experiencing or enduring. And I would love to hear what you all think about Frankl’s work and approach in the comments!

And if you found this helpful (or even moderately interesting), as always share and subscribe!

Thanks for this review. Man’s Search for Meaning can change your life. Will now read this book.