I’m at the PPE Society conference in New Orleans this weekend and gave a talk yesterday tying together some of the radically moderate thinking I’ve been doing lately.

These talks are a great way to figure out what I don’t understand about my own arguments and what I understand but I’m not communicating well to other people.

One question from the audience that I didn’t answer well was “how is this landscape an alternative to the binary or the more complex frameworks that you’re complaining about?”

I start the presentation with the binary below, arguing that it’s not just empirically wrong, but it’s also morally wrong. It not only doesn’t reflect human political, social, and moral reality, but it leads to morally bad outcomes.

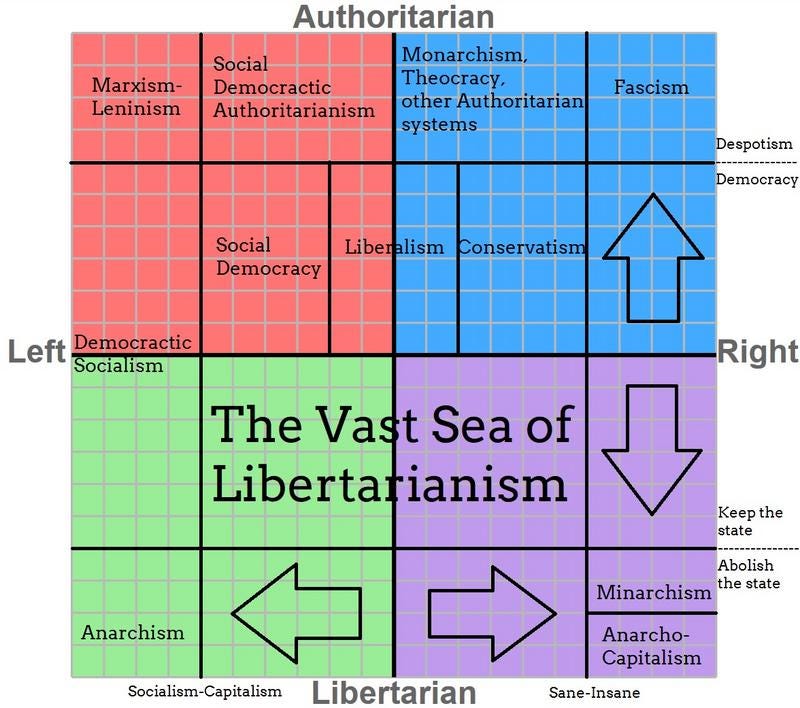

But, one of the audience members asked (or rather, the question implied), “that’s outdated, so what about more complex articulations of the political landscape, like the political compass?”

So what about the political compass above? Isn’t it more complex? Doesn’t it have three dimensions? Isn’t it more accurate? Even more specifically, the question was, “If this isn’t helpful, what’s your alternative? Where do values map onto your landscape?”

This question goes to the heart of the entire project, so I’m glad this person asked. It was clear that he thought I was presenting the complex landscape as a *different* way to locate or organize political beliefs. And that’s exactly what I’m *not* doing.

The radically moderate landscape isn’t an alternative to binaries or compasses at all, but a radical rejection of that way of thinking about politics. And that’s because social, political, and moral values don’t map neatly onto human life the way we think they do. There are no permanent locations of clusters of political ideas because that’s not how humans navigate their shared world. And, I’ll argue, as helpful as these tools are for intellectuals trying to map out the broad landscape of political ideas, they may be actively harmful in practice.

Are binaries/compasses accurate reflections of real human moral/social/political worlds?

Let’s start with the empirical case.

There is no stable location of any of these political values in the real human social, political, and moral world. We can distort things in order to shove events and people into these categories, but it’s always a distortion because it requires jettisoning so much complexity along the way.

The real social, moral and political landscape looks a lot more like the one at the top of the page. There are lots of ways to navigate that landscape, lots of decisions that need to be made, and many idiosyncratic values and goals that might animate those decisions. Pluralism runs deep in that landscape.

Moreover, even the most complex of the political paradigms don’t have a fourth dimension, which means that they locate people and human problems at a particular point in time. But social, moral, and political problems morph in really important ways over time.

To be fair, the goal of the political compass isn’t really to think about the entire human social, political and moral landscape. It’s (usually) a way to think about the power of the state or how particular politicians or political thinkers think about the power of the state. And in that very narrow sense, it can be useful. But too often we expand the compass or the binary and stretch it into areas of human social life where it has no real business going.

There are a range of complex human social, moral, and political problems where the compass doesn’t really help us locate anything like solutions. Children and the family, the mentally ill or severely disabled, small local communities, and friendships are all areas where the compass fails to give us much in the way of guidance.

But, someone might reply, that’s only because you’re using it in a way that it’s not meant to be used! Sure, that’s true. But that’s how many people *do* use it. Precisely because the political spectrum or compass is a convenient way to think about the political world it becomes tempting to place oneself on it and once you do that it’s much easier for tribalism to kick in. Once that’s kicked in it’s even more tempting to try to align your beliefs to your particular location on the spectrum, without realizing that you’re distorting yourself in the process.

The political compass is a lot like the body mass index or BMI in that sense. BMI used to be a basic and somewhat helpful screening tool - it was meant as a way to invite someone to ask more questions or do some more digging. But precisely because it was so simple, it very quickly became a diagnostic tool, labeling someone as obese simply based on their height-to-weight ratio. This is obviously very dumb because a simple height-to-weight ratio obscures an enormous amount of important variation, including muscle mass and bone density and that variation is crucial to assessing any person’s actual health status. And that’s very much the case for the political spectrum or compass too. It might be helpful as a first-round screening tool, but when we accept it as a fully accurate depiction of our social, moral, and political landscape we lose all the complexity that makes that landscape meaningful.

Academics, pundits, and wonks think about the political world in terms of spectrums because it’s a convenient way of organizing our ideas. Ironically, that convenience ends up obscuring a lot of truth and a lot of complexity. And that obscuring can actually be harmful.

Do binaries/compasses help us make better decisions?

Elites are far more polarized than the rest of the population and that may be at least in part because our simple tool has lured us into thinking about ourselves on these kinds of spectrums. As another audience member pointed out, and which I argued in a somewhat different way not long ago, binaries and even the more complex political compass trick us into thinking that the people on the other side of the binary or the compass are wrong, bad or even our enemies. They animate our tribalism, which in turn gets us thinking about political problems and their solutions in polarized terms. Once you’ve identified a politician as authoritarian, you’re much less likely to accept any of her policies, even if some of them happen to not be authoritarian at all.

The important questions we want to ask about these binaries and compasses are: Do they make us better humans? Do they help us navigate our landscape better? Do they provide better outcomes for humans trying to navigate their worlds?

The answer is “probably not.” I can’t think of any examples of real-world situations where someone’s location on a political compass helped them make a more humane decision, particularly in the real world. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen, but it’s probably not common. If anything, locating politicians and voters and ourselves in a stagnant value framework means that we’ve pinned them and ourselves like preserved butterflies in a particular political context. We’re no longer moving through an environment and making decisions together about how to navigate that environment, but we’re stuck. And if we’re stuck we’re not thinking creatively about how to solve deeply important human problems and we’re not working with people who we see as located in an incompatible part of the political spectrum.

Unfortunately, the political compass is probably here to stay. Because it’s convenient and easy, we’ll still stick people on it and it will continue to animate tribalism and create political enemies when what we need most right now is creative four dimensional thinking. We need people building bridges and clearing away barriers and asking other people what they want out of our shared landscape, which we’re not going to do if we’re pointing at each other across invisible lines. So I’m not sure what the solution is, other than to keep pointing out the complexity and beauty and messiness and colorfulness of our shared moral, political and social landscape in the hopes that it can lead us to a better way.

There’s a lot more to say here and there were some other really helpful questions that I’ll tackle in subsequent posts, but I’ll leave this question for readers and hope that they respond in the comments: is the political spectrum or compass actually helpful? If so, when and in what contexts? And if not, how do we convince people to let it go?

As always, leave a comment, subscribe and share!

These schemas (political spectrum, political compass) are mostly helpful because they are diagrammatic. People think in diagrams, which bring abstract ideas into clearer focus. People also tend to think in dualisms and hierarchies rather than in hybrids. But a feedback loop exists between the "spectrum" or the compass and how people self identify politically. In other words, I've always imagined myself center-left on the political spectrum. The political compass told me I was leaning left-libertarian, and I've absorbed that designation into my identity. But is it true?

The political compass actually needs two additional dimensions to become more accurate. If the current compass describes political freedom in the X axis and economic freedom in the Y axis, it needs a Z-axis for personal freedom. And it needs to operate in a fourth dimension, in time, as well. This accords with an idea of being as unstable, a process of becoming rather than a fixed quantity.

A theory is helpful if it captures enough of the world to at least illuminate whatever problem one is trying to solve. A problem I once had was trying to explain to my fellow students how libertarianism is not simply “right-wing” (along with fascism, racism, etc.). A version of the political compass seemed to solve that problem in many cases: https://jclester.substack.com/p/the-political-compass-and-why-libertarianism