Thoughts and Prayers in 4D

Tragedy requires humanity, not polarized memes.

As the mother of three young girls who are all heading away to sleep away camp this summer, I watched the news this past week with a combination of horror and sadness.

I also watched as the predictable politicization of deep human tragedy took over the airwaves.

I try to avoid getting angry at social media stupidity, but a lot of the internet commentary this week made me very very angry.

Before we even knew the final death toll, before families even had answers about the locations of their loved ones, before mothers and fathers even knew if their worst nightmares had really come true, pundits and activists and influencers felt the need to make claims about what families in their darkest hour want and need.

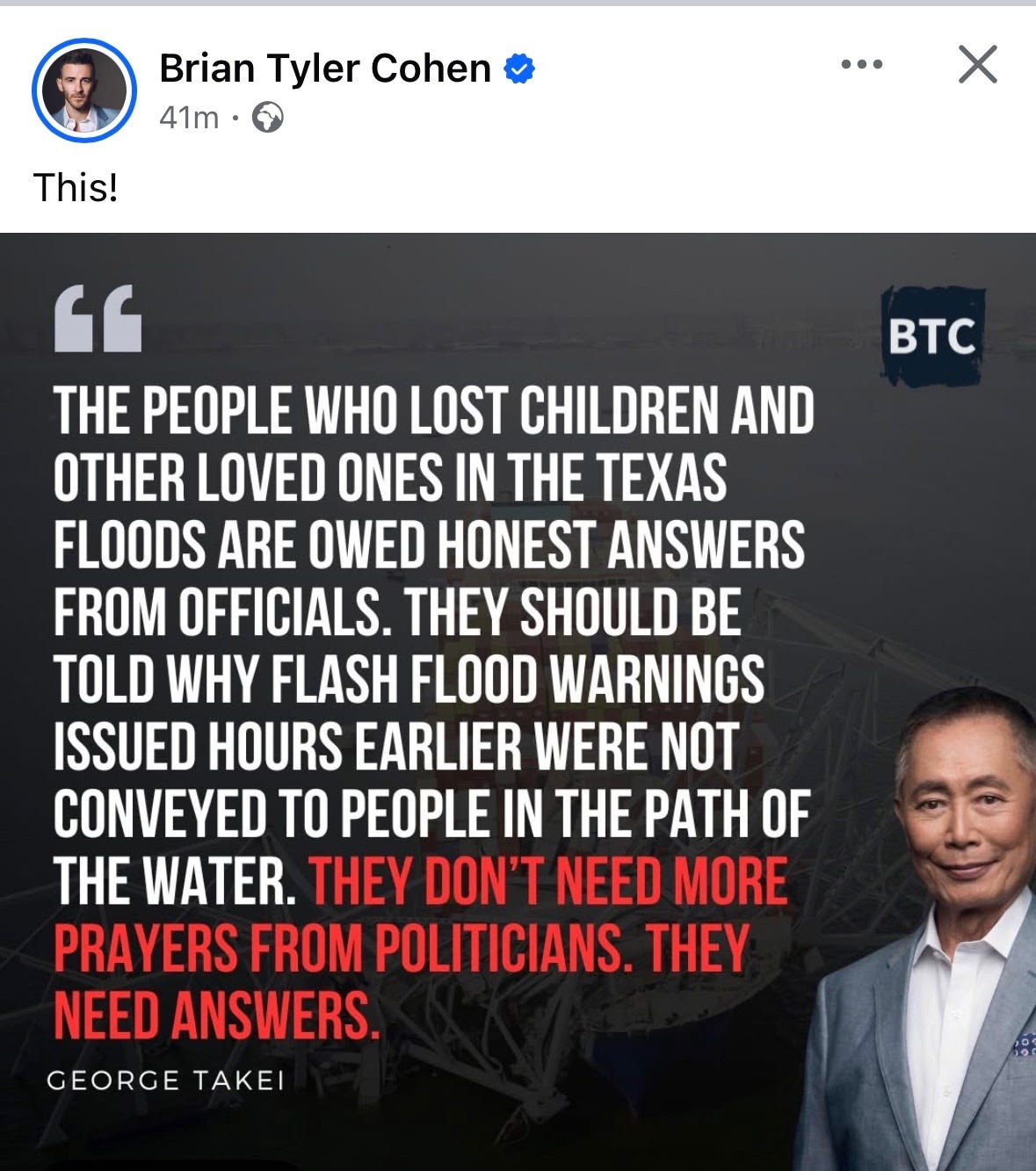

Exhibit A is the left-leaning echo chamber combo of Brian Tyler Cohen and George Takei:

This one made me particularly angry because it came out early in the week, before we could know much of anything at all.

As a mother I can only begin to comprehend the losses these families are facing and I certainly don’t know what they want or need right now. I’m also not a meteorologist or an investigative reporter or a policy analyst. And neither is George Takei.

Downplaying the power of prayer on behalf of parents

who have nothing left but an appeal to heaven

is not empathy.

But as a mother I do have some thoughts for those tempted to politicize the deaths of little girls by speaking for families they don’t know and whose losses they clearly aren’t even trying to imagine.

Polarized Empathy Isn’t Empathy At All

First, whatever your political affiliation, prayers and accountability aren’t mutually incompatible.

Prayers aren’t avoidance of responsibility or a political statement (at least not necessarily).

Prayers are a communal acknowledgement of tragedy and a communal appeal to a higher power. Random internet commentators and meme creators don’t have to believe in them for them to be meaningful for the people who receive them. And public requests for prayers can be deeply meaningful to families even when they come from political figures we don’t happen to like. We, random internet commentators, don’t get to decide when prayers are needed or not.

Second, and more generally, we don’t (ever) get to decide what other humans need or want in their darkest hour. And even more critically, those needs and wants likely do not fall onto a simple political binary. And they certainly don’t neatly align with whatever our political ideology happens to be.

Neither George Takei nor I nor anyone else gets to decide for those families what they need or don’t need. Only they get to decide that. And none of us should use these families’ grief to score political points.

Third, chances are good these families desperately need and want different things. Some likely find some amount of solace in the prayers of everyone from Governor Abbott to Pope Leo. These prayers remind them they are not alone in their unbearable agony, that neither God nor their communities have abandoned them.

Others may be consumed by anger, even rage, at the combination of factors that ripped their lives apart. They want vengeance, accountability, or just oblivion from gut-wrenching grief.

Others may be numb or bewildered, unable to even think.

Others wait on a uniquely tortuous cliff of uncertainty, torn between the desperation of hope and the increasing likelihood of their greatest fear.

Chances are good many of them don’t even know what they need right now and that’s ok too.

I do not know what any of these particular parents need because I do not know the depth of their loss, their values and personalities, their communities, let alone how they are managing to take their next breath or face tomorrow.

But I do know a few things.

Claiming to speak for parents who are still awaiting news of their children’s fates is not advocacy.

Arguing that prayers and accountability are mutually exclusive is not activism.

Downplaying the power of prayer on behalf of parents who have nothing left but an appeal to heaven is not empathy.

More than anything, now is not the time for anyone to weigh in on what these parents need but those parents themselves. Unless you can deliver a casserole or wade through underbrush searching for the body of a lost child or have years of expertise in disaster mitigation policy you have no business weighing in at all. And you certainly have no business doing it with memes that translate deep human loss into algorithmic clickbait.

Let the meteorologists and policy analysts and search and rescue crews and investigative journalists do their work while the parents awaiting answers find whatever solace they can in God and each other and their communities. Let the parents who already have answers find a way to bury their children without your internet commentary or your memes.

What We Can Do

While it is not our job to tell these parents what they need, it can be our job to let them know that they are in our thoughts and yes, in our prayers. Perhaps especially in our prayers, given the religious background of the girls who were swept away.

One beautiful thing about prayers is that they are (or can be) politically neutral. As a mother, I can simultaneously pray for the mothers of children in Gaza and the mothers of Israeli hostages and for mothers everywhere who have lost their children to avoidable and unavoidable tragedies.

I can also pair my prayers with any number of tangible acts, from sending money to writing legislators to advocating for policy change.

But I don’t get to claim to speak for people I don’t know and I don’t get to demand answers that fit my personal political values. I don’t get to use other people’s tragedies that way.

What I can do is be human.

And sometimes, as much as it pains our (also human) hubris to admit it, the most human thing we can do is kneel down precisely because there’s nothing else useful we can do in that particular moment.

We can and should all think very carefully before we click “like” or “share” on political memes and posts of all kinds, but particular those dealing with someone’s deepest pain. No matter how well-meaning our intent, we need to dig deeper and question whether we are really speaking on behalf of the people who are suffering most or whether we’re using someone else’s tragedy as a way to signal and affirm our existing political beliefs.

Human tragedy and grief doesn’t fit into simple binaries and we should be very (very) careful about not forcing it to do so.

This is true not only because forcing tragedy into binaries harms those who can least afford it, but also because it distorts our humanity when it’s needed most.

Leave a Comment

As always, let me know what you think. This one was tough.

One thing that is so obvious that it seems silly even to say it is that regardless of what you think about the politics of a country or a region, nobody is morally culpable for where they happen to be born or where they happen to reside.

And yet the public discourse is sufficiently demented that a lot of people don't seem to be willing to follow this very obvious point to its logical conclusions.

That's why you have college kids in the US yelling "Free Palestine" in response to the October 7th attacks, as if anyone who lives in Israel deserves to be the victim of a terrorist attack. It's why you have people claiming on televised news broadcasts that "there are no Palestinian civilians" (apparently even Palestinians who are two months old don't count as civilians). It's why there are conservatives who mock victims of violent crimes because if they lived in a blue city they must have "voted for" what happened to them and brought it upon themselves (as if all 1.5 million people who live in Manhattan must have exactly the same political beliefs. . . and as if there exists a set of policies that, if implemented, would ensure that no violent crime would ever happen). And it's why cartoonists and celebrities mock victims of natural disasters in red states.

The logic of these notions doesn't check out if you spend all of two seconds thinking about it.

Using a tragedy as political theatre is pretty yucky. The “FAFO” type comments especially. But I wonder if the comments along the lines of the one you called out are the result of a repeated pattern- one where the people who have the power to make a positive change in the aftermath of a tragic situation send their thoughts and prayers and then do nothing else.

As a public school teacher this makes me think of legislators after a school shooting. So many thoughts and prayers are in press releases of congress people and government officials, but when the time comes to pass legislation that could prevent another school shooting it seems those last dead kids aren’t in their thoughts anymore.

There should be serious investigations into how this flooding happened and where the communication breakdown was. And the findings should result in changes to be better prepared in the future. There’s nothing wrong with the thoughts and prayers- but it can’t be the only response. Actions are needed too, and people with a platform to call for those actions should use it.